More on:

Another year, another survey: the Modern Language Association (MLA) has released its quadrennial language enrollments survey of foreign languages in U.S. higher education. I’m sorry to report that American students continue to display very low interest in Indian languages. This continues a pattern going back decades. Despite the Indian economy’s rapid growth, and the increase in U.S.-India diplomatic ties, students in U.S. colleges and universities are not signing up for Indian languages at remotely the scale languages like Arabic, Chinese, or Korean experience.

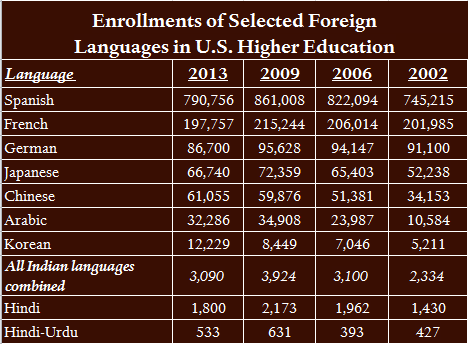

First, the context: during 2013, the year the newly-released data covers, foreign language enrollments dropped overall by 6.7 percent since the prior survey year, 2009. Long-established and highly studied languages in the United States—Spanish, French, and German—all saw enrollment drops from 2009 to 2013, whereas previous years had seen upward trajectories. Only four languages saw increases in their enrollments from 2009 to 2013: Korean, with a whopping nearly 45 percent, American Sign Language, Portugese, and Chinese.

It’s not surprising that the most studied foreign language in the United States is Spanish, with nearly 800,000 enrollments, and French occupies the second slot with nearly 200,000. But the trends since 2002 tell a story about twin interests in Asia’s economic rise and national security concerns.

Japanese has enjoyed substantial enrollments going back to the 1970s, with a doubling from around 23,000 in 1986 to nearly 46,000 in 1990. In the years since then it has been on a consistent uptick, 2013 excepted. Chinese has similarly been on a slow increase from the late 1970s as well, with a more dramatic 50 percent bump from 2002 to 2006. Korean enrollments were below 1,000 in 1986, with slow increases through 2009, and then the surprise 44 percent increase in 2013. Arabic enrollments hovered from 3,000 to around 5,000 from 1977 to 1998, and then doubled by 2002 to a little more than 10,500, and then doubled again by 2006 to nearly 24,000. (All data retrieved from MLA.org’s interactive enrollments database.)

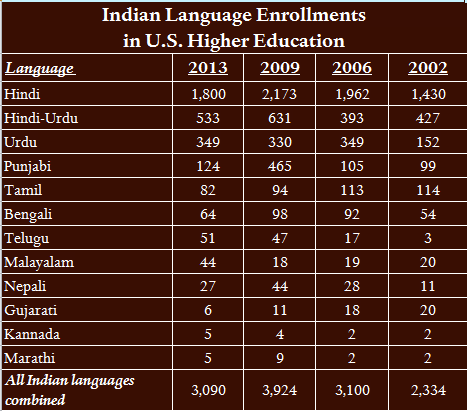

Indian languages follow a path less traveled. The big post-9/11 national security interest that resulted in many more Americans studying Arabic did not have the same impact on Indian languages. (And frankly, the uptick for Pakistani languages still resulted in enrollments under 500 for every Pakistani language—a topic for another discussion.) Nor has India’s economic rise resulted in the dramatic growth in numbers languages like Japanese, Chinese, and Korean have seen. Of course it’s harder to compare India’s many languages with each of these, but even when including all the Indian language enrollments in the United States combined, the number still doesn’t cross 4,000. For 2013, Indian language enrollments dropped to 3,090 from the 3,924 of 2009.

This is very slim compared with the scale of study that Japanese (nearly 67,000), Chinese (over 61,000), and Korean (more than 12,000) had in the United States during 2013. And it has been like this as long as I’ve been watching. (The pattern appears as well in U.S. study abroad destinations, where India does not even make the top ten.) Whenever I make this comparative statement, I receive emails and comments from people noting that English is an Indian language, so why should anyone bother with learning others? It’s true that English is an official language of India, along with Hindi, and that is not my argument. In the business world, people speak English across Asia, so the issue isn’t narrowly one of ability to communicate. Rather, it’s more an observation of the priority American students appear to place on developing a deeper and more place-specific knowledge of a country. In the case of India and its official and many other languages, I’m afraid that Americans do not see these as a high priority compared with other choices.

Top photo credit: Indic Scripts, 2013. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Follow me on Twitter: @AyresAlyssa

More on:

Online Store

Online Store